The names of Poland’s towns and streets were Germanized. Speaking Polish in public in the incorporated provinces was prohibited. In the predominantly German-populated area of Gdansk (renamed Danzig) the public use of Polish language became a capital offence on September 4, 1939. On August 22, 1939, a week before his attack on Poland, Hitler exhorted his nation: "Kill without pity or mercy all men, women and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the living space we need." As many as 200,000 Polish children, deemed to have "Germanic" (Aryan) features, were forcibly taken to Germany to be raised as Germans, and had their birth records falsified. Very few of these children were reunited with their families after the war. More than 500 towns and villages were burned, over 16 thousand persons, mostly Polish Christians, were killed in 714 mass executions of which 60% were carried out by the Wehrmacht (German army) and 40% by the SS and Gestapo. In Bydgoszcz the first victims were boy scouts from 12 to 16 years old, shot in the marketplace. All this happened in the first eight weeks of the war. See Richard C. Lucas, The Forgotten Holocaust; The Poles under German Occupation. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky [c1986]. In the East, the Russians, collaborating with the Germans (Hitler-Stalin pact of Aug. 23, 1939) attacked Poland on September 17, 1939, and occupied the eastern part of Poland until June 1941. Massive killings followed, among them 21,857 officers, mostly reserve members of the army, police and frontier guards, whose bodies were found later in Katyn, Miednoye, Kharkov, Tver. Other bodies from these massacres have never been found. About two million Poles, mostly members of the intelligentsia, were deported to Siberia or to Kazakhstan in Central Asia. More than half never returned; thousands were killed in the fighting and over 452,000 became POWs in Soviet Russia. Poland disappeared from the European map, divided between Third Reich and the Soviet Union.

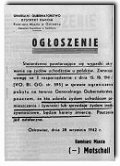

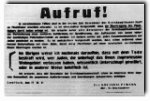

According to the AB German Plan, Poles were to become a people without education, slaves for the German overlords. Secondary schools were closed; studying, keeping radios, or arms of any kind, or practicing any kind of trade were prohibited under the threat of death. In 1988, the public prosecutor, Waclaw Bielawski, from the Main Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against the Polish Nation, issued a list of 1,181 names of Poles who had been killed for helping Jews during World War II. In 1997, the Main Commission – The Institute of National Memory and The Polish Society for The Righteous Among the Nations in Warsaw, published Part III in the series Those Who Helped: Polish Rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. It reduced the list of 1,181 names to only 704, by accepting only those whose accounts could be independently corroborated and verified fifty years later. The publication also included the names of more than 5,400 Poles, who have been recognized by the Israeli Yad Vashem Institute – The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, as “Righteous Among the Nations.” About 17,000 people of 34 nationalities were similarly honored. In Western Europe the automatic death sentence for help rendered to Jews did not exist and applying it to a whole family or neighbors was unthinkable. The reign of terror that organized in Poland was completely isolated, and unimaginable in the West.

Saving Jews was very difficult, as about 85% of Poland’s Jews either did not speak Polish or spoke a dialect. In many cases, Jews were distinguished by their appearance.

The stories of the rescuers are a shining example of the most selfless sacrifice, surpassing in its heroism that of all the soldiers on the battlefield, whom we commemorate each November. In fact the soldier must fight; he cannot refuse. He is sustained by the entire military organization and his efforts are mostly limited to battles that have a clear beginning and end. He is paid and given the food, supplies and weapons that he needs.

Who of us would do it today, especially in the above mentioned conditions? Wartime Rescue of Jews by the Polish Catholic Clergy. The Testimony of Survivors. Compiled by Mark Paul. Polish Educational Foundation in North America, Toronto 2010. (Requires Acrobat Reader). |

|

Those Who Paid with Their Lives (704 NAMES) According to the vol. III of "Those Who Helped" of 1997, by the Main Commission mentioned here. Due to the omission of Polish diacritical marks the alphabetical order is slightly different from that in the English language. (Remarks about the Polish alphabetical order). A|B|C|D|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|R|S|T|U|W|Z – ANNEX

Mass executions – the so-called 'pacifications' of villages List of approximately 5,400 Poles recognized as "Righteous Among the Nations" title bestowed by Yad Vashem of the State of Israel (as of Dec. 31, 1999). Due to the omission of the Polish diacritical marks the alphabetical order of names is slightly different from the English one. Notes about the names are based on the Bibliography and on my own documentation.

A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|R|S|T|U|V|W|Z

Name search – type the name you are searching for: Bibliography

|